Written by Ross Paterson, our Finance Officer.

The reasons why people use drugs are numerous. For some, they serve as a form of escape, often leading to harmful patterns of use usually associated with destructive social and personal consequences. Others use drugs for functional purposes, as a means to improve productivity and to overcome challenges associated with various health conditions (for instance, the use of cannabis to treat chronic pain, or of amphetamines to treat ADHD). We might call this (self-) medication. Others use drugs as a tool for spiritual exploration, from ancient ayahuasca rituals in Amazonian countries to the guided psychedelic journeys led by the new age, self-described shamans of today. However, somewhat ironically, it seems that in many ways the most overlooked form of drug use is the one which is most common – the use of drugs for purely hedonistic, recreational purposes. In short: the use of drugs for pleasure.

In drug policy discussions, there tends to be an enormous focus on the most harmful forms of drug use, such as that associated with addiction, and how policies should respond to this with targeted harm reduction interventions such as opioid substitution therapy (OST) and needle exchange services to improve health outcomes for such people. And rightly so. These are the groups for whom drug use poses the most acute threat to the health and to the life of the individual. I need not point out, for example, the well-known association between opioids and death by overdose. It is right that the majority of resources are directed at these higher risk populations.

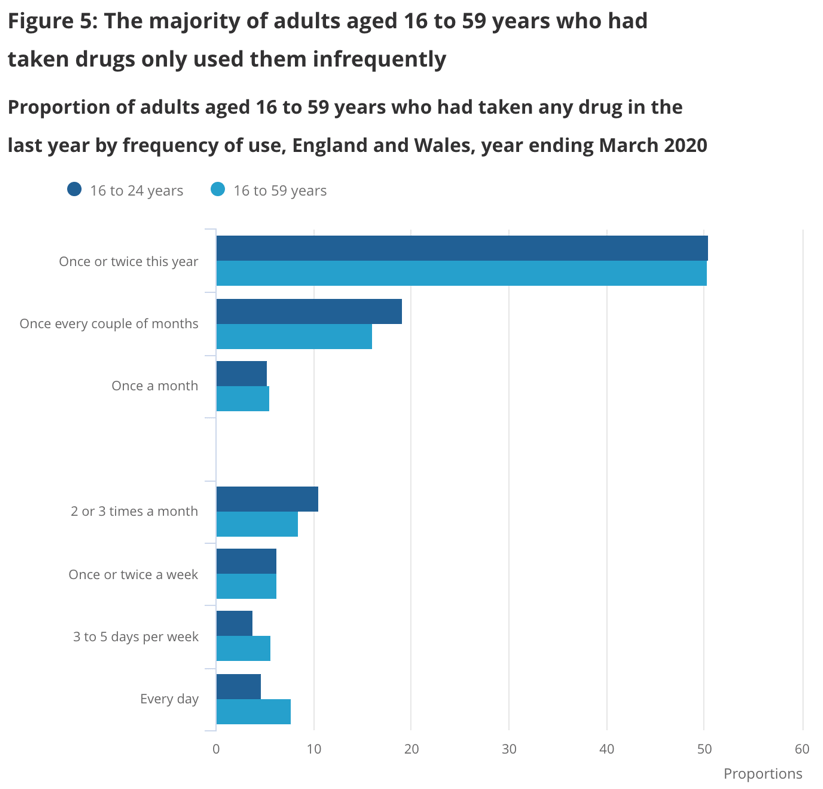

However, despite this justified prioritisation, it still feels somewhat ironic that less harmful, more recreational forms of drug use remain so overlooked, despite the fact that this form of use pertains to the vast majority of people who use drugs (PWUD) overall. This assumption is supported by even a cursory glance at survey data relating to patterns of drug use. For example, in the 2020 Crime Survey for England and Wales, 9.4% of adults age 16-59 indicated they had used illegal drugs in the last year. Of those respondents, only 7.7% reported daily use, and only 5.7% reported using drugs 3 to 5 days per week. In contrast, the vast majority of PWUD in this survey used drugs only very occasionally, with 50.4% using them only once or twice per year, and 16.1% using them once every couple of months (see figure 1).

So, how can it be that such a sizeable demographic is so often left behind when we discuss PWUD? They account for the majority, and yet they often feel like a mere afterthought. Personally, I think this relates to the fact that one of the most fundamental features of drugs is also one of the most overlooked – that they’re fun.

Pleasure in general sometimes feels like a taboo subject. We see this in other conversations to a certain extent as well. For example, in conversations about sex (particularly in relation to female sexual pleasure). There is almost a reluctance to acknowledge that the human experience is largely driven by the pursuit of pleasure. In Freudian terms, this is known as the pleasure principle – the idea that humans naturally seek pleasure to satisfy their biological and psychological needs – and it is this pursuit which precipitates the use of drugs for so many in the first place. In his 2005 book Intoxication: The Universal Pursuit of Mind-Altering Substances, psychopharmacologist Ronald K. Siegel points out that the consumption of mind-altering substances can be traced back to every age in every part of the world. And this is not specific only to humans – many animal species have been observed exhibiting drug-seeking behaviour, from cats getting high on catnip to dolphins passing around puffer fish, from lemurs getting stoned on toxic millipedes to a huge number of species including monkeys, elephants, ostriches, giraffes, meerkats and others actively seeking fermented marula fruits to enjoy an alcohol-induced state of intoxication. For Siegel, the pursuit of intoxication is so natural and universal that he considers it to be the ‘fourth drive’ of human (and animal) behaviour after food, water and sex.

Whether or not you may support Siegel’s contention, ancient examples of substance use dating back as far as 10,000 years make it difficult to dispute the idea that intoxication is a fundamental aspect of the human experience. Despite this, over a number of centuries, humans have predictably done what they do best: ascribe moral value to an otherwise uncontroversial, unarguably natural phenomenon, resulting in myriad consequences such as shame, stigma, discrimination, social exclusion, and policy-induced suffering. What the Church might once have described as a sin, in secular society we now describe as a moral failure. It is for this reason, I believe, that less harmful, more recreational forms of drug use remain largely excluded from public discourse around drugs, despite its high prevalence. To talk candidly about recreational drug use would require one to accept the basic reality that people largely consume drugs because they produce pleasure, and that would be to undermine the “Just Say No” philosophy underpinning the prohibition model. Grown-up conversations acknowledging the role of pleasure regarding drugs sadly remain few and far between.

Nevertheless, enter a typical bar or nightclub on a Friday night and, whether you’re aware of it or not, you are entering a cathedral of indulgence, surrounded on all sides by people using illicit mind-altering chemicals. I often find it rather amusing whenever I visit a bar or nightclub bathroom only to find a long queue for the cubicles while the urinals remain conspicuously available. But the lack of attention to this form of recreational drug use has led to those who use drugs in these environments – predominantly young people – being underserved. Prohibition has, as it so often does, led to countless deaths as a result of adulteration and variable purity. To use ecstasy as an example, the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction reported that while the average dose of MDMA per tablet rose from 50-80mg in the 1990s to 125mg in the 2010s, “super pills” containing 270-340mg (around three times the recommended dose) are not uncommon, with large variations in dosage in similar looking tablets. Similarly, potentially life-threatening adulterants such as PMA are frequently detected in tablets.

Both adulteration and unpredictable purity have contributed to a substantial number of drug-related deaths over the years, often leading to knee-jerk, reactionary responses such as shutting down nightlife venues altogether or introducing stricter, more invasive search procedures before entry. Such responses, of course, do nothing to prevent the reoccurrence of such tragic incidents, often leading to myriad other harms such as nervous revellers choosing to ingest all their drugs at once before passing security, for fear of being detected and facing criminal justice consequences.

In drug policy reform advocacy circles, these issues are well-acknowledged and the solution is blindingly obvious: we must abandon these backward and harmful tactics and push for more free, on-the-spot drug testing services in settings such as bars, nightclubs and festivals. Pioneering projects such as The Loop have been doing precisely that for years, saving countless lives in the process. At one UK festival alone, in 2016, drug-related hospital admissions dropped by a massive 95% on the previous year thanks to The Loop’s service, which found one in every five samples were not as described by dealers and that two-thirds of festival-goers who returned a negative sample result chose not to ingest the substance.

So why aren’t these services much more widely available? Why are policy-makers so resistant to these pioneering harm reduction services, despite such irrefutable evidence of their enormous effectiveness? It seems quite uncontroversial to want to reduce harm for those who “dare” to enhance their experience with substances beyond alcohol, for whom the consumption of street drugs amounts to a roll of the dice. The answer can be traced back to the moral assertion that drugs = bad, no matter what, and the curious reluctance to accept the natural human impulse to seek to maximise the pleasure associated with festival and nightlife settings. In the eyes of many policy-makers, drug use amounts to a form of sin. Thus, to accept the relatively innocuous reality that many young people would like to safely enjoy themselves on a night out [*gasps*] would be to endorse behaviour which so many resources have been dedicated to painting as a moral failure, something fundamentally wrong.

Indeed, it is precisely these such assertions which form the bedrock of prohibition in the first instance. To ban a perfectly natural behaviour, one must attach to it a moral dimension and relentlessly shame and punish those who engage in it. The LGBT+ community may know a thing or two about that. But as time marches forward, attitudes tend to evolve with it. Attitudes among the public towards drug policy, at least in some Western countries where the ‘War on Drugs’ rages on (like the UK and the US) reflect this fact. But thus far, policy-makers have largely remained behind the curve, maintaining the catastrophic, self-defeating approaches which remain the dominant drug policy blueprint globally.

In the absence of on-the-spot drug-testing services, drug use will go on just as it always has done, with young people exposed to unnecessary policy-induced risk. This absurd moral posturing must end if we are to begin a mature dialogue about why many people choose to use drugs in the first place – because they feel good – and design policy to reduce harm accordingly for all PWUD, including those who use them on a purely recreational basis. Young people would inevitably be one of the main beneficiaries of any such policy shift, and their right to safe consumption deserves parity with OST patients’ right to safely prescribed opioid medication. People like drugs, and we know that young people will continue to use them despite whether or not some old white man in a suit approves of it. There must be a concerted effort to engage in honest, frank discourse about the pleasure associated with drugs if we are to advocate for evidence-based policies to protect the health of these otherwise perfectly normal young members of society. So, to borrow a Simpsons quote: won’t somebody please think of the children?